“Original Phoenix Sun” Dick Van Arsdale rebounds from a stroke with an assist from painting..

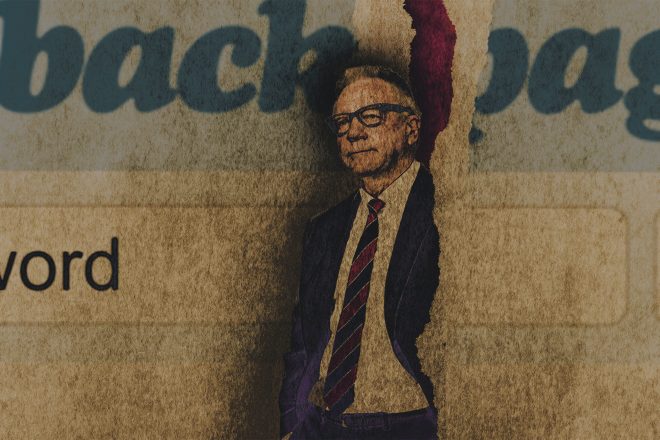

In the world of sports, they like to say “it ain’t over ‘til it’s over.” Few careers, or lives, illustrate this maxim as startlingly as the past few years in the life of Phoenix Suns legend Dick Van Arsdale. The old line about one door closing and another door opening gets a pretty spectacular demonstration from Van Arsdale, too.

Known as “The Original Sun,” a moniker he earned by scoring the Phoenix Suns’ first point in 1968, Van Arsdale was an All-Star guard who played nine years for the franchise, ending his on-court career in 1977 after playing alongside his identical twin brother, Tom. He went on to serve the Suns in several other capacities over the years, including a stint from the late ‘70s until the early ‘90s as a Suns broadcaster, providing color commentary alongside the seamless play-by-play of Al McCoy. Audio of his broadcast work from those years reveals a smooth, easygoing, confident professional speaker. That capability was taken from him one morning in November 2005, when Van Arsdale’s wife Barbara woke to find him standing at the door, seemingly perplexed by how to open it. He was unable to put words together, either. “I was naked. I couldn’t talk to my wife, I couldn’t talk to anybody,” recalls Van Arsdale of that morning. “I couldn’t write anything, I couldn’t tell anything.”

Van Arsdale’s wife and his brother Tom took him to Scottsdale Healthcare, where Van Arsdale learned he’d had a stroke. “I was in the hospital for about seven days,” Van Arsdale says. “And I got a little better.”

You wouldn’t notice the impairment right away – at first he just sounds like the classic laconic Midwesterner, favoring monosyllables – but Van Arsdale still has some difficulty getting words out. At 70, he’s white-haired but still as towering and healthy-looking as ever. But every few sentences, you can see him pause to search for a word. If he can’t find it, sometimes he just shrugs and smiles apologetically. In most cases, you can tell what he means.

On the upside, though, he’s become a fine artist.

The office walls of Van Arsdale Properties, the real estate company he owns in Old Town Scottsdale, are covered with pictures in pen-and-ink or colored pencil. They vary in style and subject, but generally fall into two categories: black-on-white images of stylized figures representing basketballs, hoops, scoreboards, players and crowds, and rural scenes featuring farmhouses, barns, water towers, rusty trucks and tractors. Van Arsdale’s renderings of things like flower pots and perching owls are reminiscent of the folk-art style of Grandma Moses, but with more vibrant colors. Both motifs speak to Van Arsdale’s life: his upbringing in farm-filled Indiana, and his basketball career.

Van Arsdale played hoops at the University of Indiana at Bloomington before spending three seasons with the New York Knicks. He landed in Phoenix via the 1968 NBA Expansion Draft, on the first roster of the Phoenix Suns. His twin brother Tom, who’d played for various NBA teams including the Detroit Pistons, joined him on the Suns for Van Arsdale’s last season. “We were together, but the team wasn’t a very good team,” Dick recalls. “But it was great for us.”

Dick Van Arsdale’s career with the Suns didn’t end after he stopped playing. He’s held a variety of positions with the team over the decades, including interim Head Coach, General Manager and Senior VP of Player Personnel. His role as an artist has been partly facilitated by rehabilitative therapy. The art, in turn, has been therapeutic, keeping his hands busy and his brain engaged.

Getting his faculties back has been a years-long project. After his stroke, Van Arsdale began working with a speech pathologist, Sue Okun, at Scottsdale Healthcare Shea. Their sessions continue seven years later. “I see her every couple of weeks, and she really helps me out,” Van Arsdale says, adding simply, “I

love her.”

The feeling seems to be mutual. “I feel like I’m the lucky one, to have had him as patient and a friend,” Okun says. “He’s made tremendous progress. He’s gone from just being able to say a few words to being able to hold a conversation. He’s the pure example of life being about your attitude. He’s never had a ‘why me, poor me’ attitude.”

Along with speech therapy came art therapy. “I have to do something,” Van Arsdale says. “I couldn’t just do nothing.” He says he’s had no formal art training at all, and never really had much interest in it. “I just wanted to play basketball,” he says. “Basketball was my life. But,” he shrugs, “I can’t do it anymore.”

So he began to experiment with drawing – first, abstract figures in black ink, which grew more representational until they resolved themselves into geometrical little basketball guys leaping around on the court. The cheery rustic scenes, apparently inspired by his Hoosier childhood, came later, as he began to work with colored pencils. Although he didn’t grow up on a farm, Van Arsdale notes, “We had gardens. My father was a math teacher. He hated school, but he loved to garden, so I always had to help him. I hated it.”

Nonetheless, the experience seems to have made an impression on him. There’s a sunny, paradisiacal vision to these pictures, yet also a hint of wry wit – the slightest edge of a kid who hated helping his dad in the garden – to rescue them from soppy sentimentality. They’ve been part of art shows, and he’s donated them to charity.

Asked if she’s ever seen anyone else in Van Arsdale’s position discover a previously unknown talent, Sue Okun says, “I will just tell you this: I’ve been a speech pathologist for 30 years, and I’ve worked with hundreds of stroke patients, and I’ve never met a man with more remarkable talents. This is the silver lining in the stroke… He’s found his talent and he’s taken off with it.”

Van Arsdale’s new passion has been infectious. On one wall of his office are a number of competent oil paintings of rural scenes similar to his pencil drawings. “My brother did those,” he explains. Tom Van Arsdale wasn’t a Sunday painter prior to his brother’s stroke, either. “He got into it when I did,” Dick says, and holds up joined fingers. “We’re like this.”

On another wall are a couple of pretty respectable watercolor portraits. “Jim Fox, another old NBA guy, did those,” he says. But whether or not his office continues to be an artistic salon for retired basketball players, Dick Van Arsdale says he’s committed to drawing. “Art is good for me,” he says. “If I didn’t have art right now, I’d have problems.”